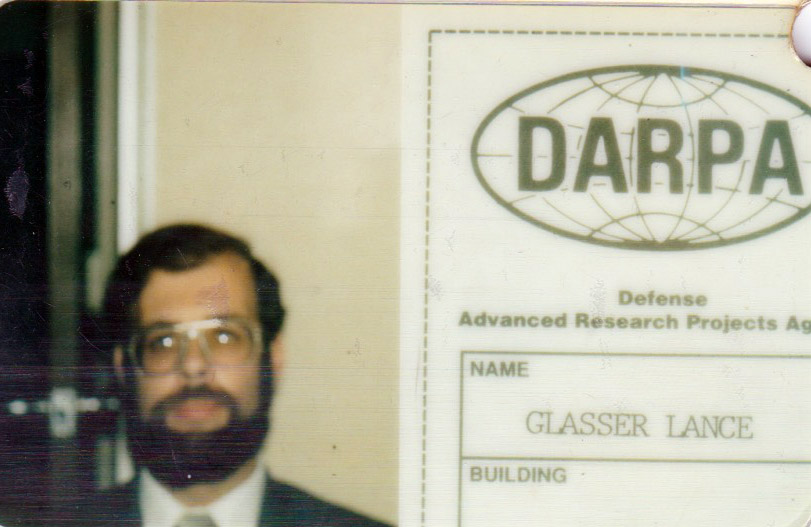

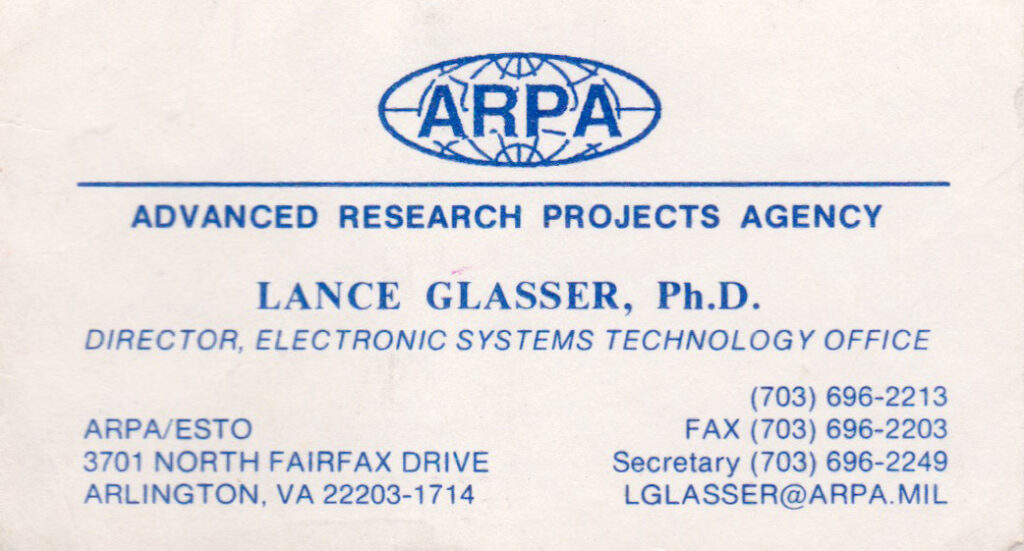

When I ran the electronics technology directorate at DARPA I had the wonderful job of examining a big percentage of all of the advanced electronics research in the country. DARPA, the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency, is the central research program arm of the US Department of Defense. It was created in response to the US surprise with the launch of Sputnik. Its mission is to create and prevent technology surprise. It has created military breakthroughs and dual-use breakthroughs. For instance, DARPA did the first stealth aircraft work in the 1970’s, but its most famous and important project was the ARPANET, later to become the Internet. (DARPA and ARPA are the same organization—the “D” comes on and off as a function of politics.) DARPA has about 200 people and about 100 program managers with a budget nearly $3B per year. It “out-sources” all of its research.

It was a great learning experience. I learned, for instance, that when you distribute half a billion dollars a year in funding, your jokes are funny and people return your phone calls. I also developed a feel for what makes a successful research team. The first key ingredient is, of course, talented people. Finding, attracting, and retaining the right people is job one. The difference between good and great is amazing.

But more than that, you also need funding. Some research organizations subdivide their funding into such small slices that no one really has critical mass and the researchers spend all their time developing proposals rather than doing research. To be successful, one needs to fund to critical mass, which is not the same as giving people everything they ask for.

You also need a connection to a real problem (at least for the sort of stuff that I cared about). See an example of such here.

So much is obvious. Another few points.

I believe that you also need to minimize the number of people who can say “no.” Committees, peer review boards, and other large assemblies of people tend to regress to the mean. If you want breakthroughs, you have to get rid of committee voting. You also need a diversity of thinking. No one, not even someone as brilliant as Sir Isaac Newton, is smart enough to see the future perfectly. At DARPA there were usually just two people who needed to say “yes” in order to get a project going. Indeed, we often sponsored programs at companies where the company’s management was not particularly supportive of a project, but we liked it. With such a process, you can encourage breakthroughs to bloom. You also inevitably end up doing some stupid stuff—which is part of the cost of being fast and daring to be great. The key is to shut down losers as soon as possible.

Another enemy of good research decisions is politics. Politics is about the power of constituencies. Who is the constituency of the new? Since it does not exist, it has no powerful constituency yet. It is just an abstraction. On the other hand, the old has had time to develop a potentially well-organized and powerful constituency. This is the reason that politics is the enemy of rapid innovation.

The last important ingredient in creating research breakthroughs is creating heterogeneous research communities. I grew to love the times when world-class researchers from Stanford, MIT, Berkeley, etc., along with leaders from government and industry, got into heated technical arguments, which often lead to high-gain brainstorming. You could actually see the field of research accelerate forward in front of your eyes. Wow.

And where should one focus ones research? As my thesis advisor, M.I.T. Institute Professor Hermann Haus, coached me several decades ago, the best place to prospect for breakthroughs is at the interface between fields, especially if at least one is evolving quickly. Discovering something fundamentally new at the heart of thermodynamics is very very hard. One needs a very long drill to reach for new oil there. On the other hand, if there has been a recent breakthrough in one area or if one research area is progressing very rapidly, one can be sure that there are many exciting things to be learned at the intersections of that dynamic area with other historically more “mature” domains. This is why people keep rediscovering that diverse interdisciplinary teams from divergent backgrounds often create the most exciting progress, once they put in the effort to learn a common vocabulary. And since, as Plato observed, “necessity [is] the mother of invention,” make sure to have lots of real problems from real customers.